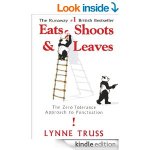

In Serial Commas and Compulsive Behavior, serial comma (aka Harvard Comma and Oxford Comma) combatants duked it out over correct usage.

On my scoreboard, the serial comma won, hands down. But journalists, Brits, and Aussies don’t all agree with me.

A Bigger Problem: Parallel Structure

But a major underlying issue compounds the serial comma problem: parallel structure.

To be grammatically correct, both serial commas and parallel structure must be right in your writing.

Constance Hale, author of Sin and Syntax: How to Craft wickedly Effective Prose (1999), reminds us of the danger of not  understanding parallel structure and appropriate punctuation:

understanding parallel structure and appropriate punctuation:

Some of the most hilarious errors in English result from phrases that aren’t properly tracked. If you don’t know what you’re doing, phrases will deliver you straight to The Danger Zone.

Want to avoid errors with serial commas and parallel structure and keep June Casagrande’s nasty old grammar snobs from picking on your writing (Grammar Snobs are Great Big Meanies, 2006)? Read on.

Look for the Lists

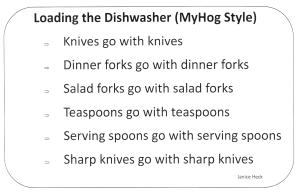

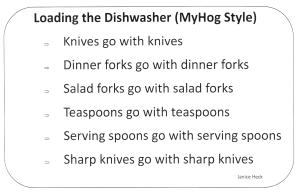

My husband (My Heck of a Guy, affectionately known as MyHog for short) is set in his ways about just how to loads the eating utensils in the dishwasher.

(Just don’t nest the utensils. They will get cleaner if they go every-which-way.)

Whatever. Makes no difference to me; he loads the dishwasher, so he can do it any way he wants.

I must admit (but don’t tell him I said this) his method of loading the dishwasher makes it easier to empty the dishwasher. Grab a handful of knives and plop them into their home base in the utensil drawer. Repeat. In six basic swoops, the utensils are happily nested in the silverware drawer.

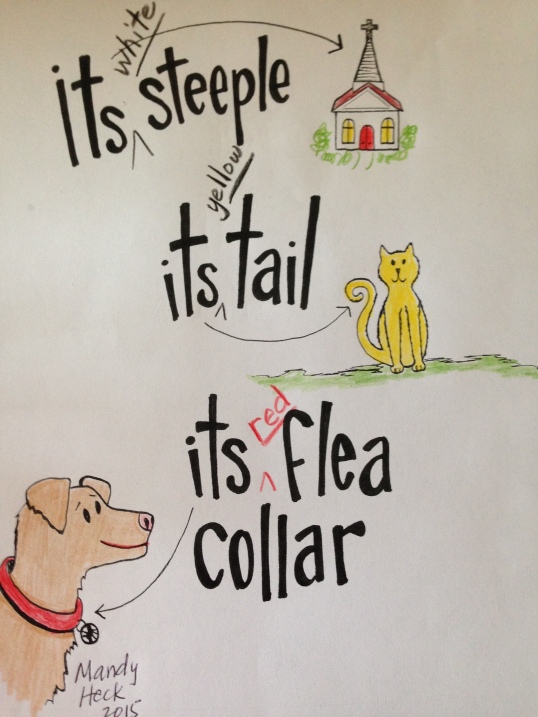

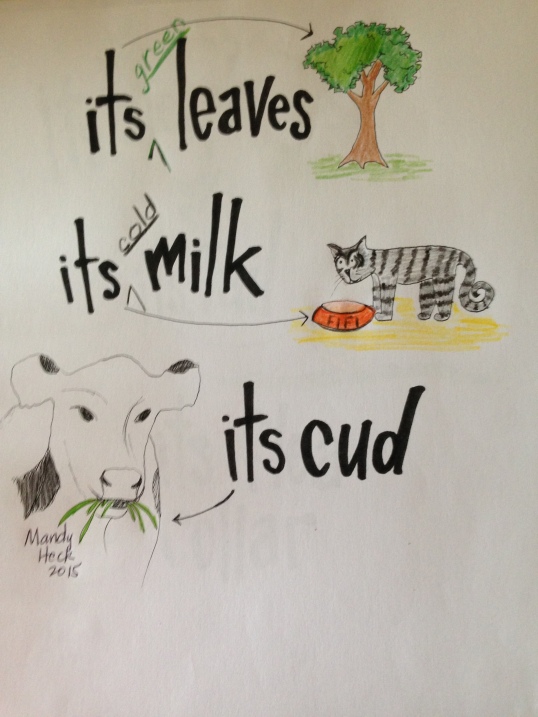

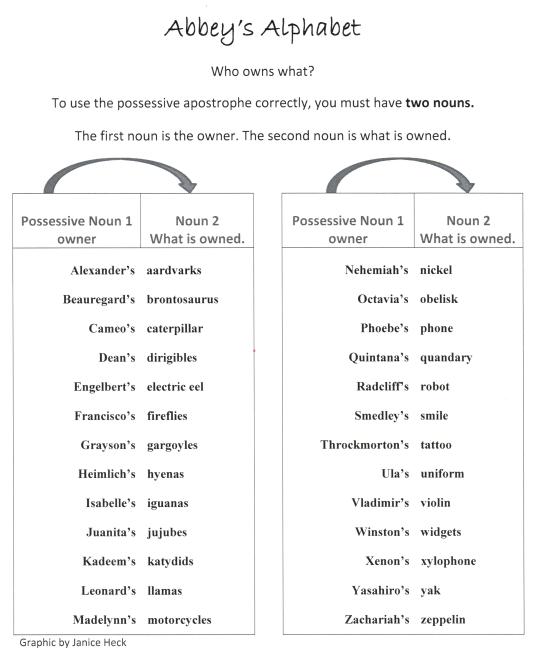

Serial Lists: Like Parts of Speech Go Together

Serial lists are like loading silverware in the dishwasher: like parts of speech go together.

These patterns, known as parallel structure, keep your writing organized and bring poetic flow to your sentences. If you mix grammatical words, phrases, or clauses in lists (non-parallel structure), you not only lose the flow of your sentence, but you become snickering fodder for the grammar snobs who lie in wait ready to pounce on any and all unsuspecting and naïve writers.

Writing lists in non-parallel structure to good writers is like throwing a teaspoon down the garbage disposal while it is running: it makes a terrible clunking noise, and you just want to make it stop.

Serial Lists in Zombie Territory

Zombies? I follow my own advice and read widely in all genres. So when a zombie book came my way, I read it…and laughed the entire way through.

New York Times bestselling author, Kevin J. Anderson, is a master at using serial lists in his book, Death Warmed Over (2012). (All quotes in this post are from this book unless otherwise noted.)

Zombie private investigator Dan Shamble, pronounced Chambeaux, despite being dead himself, hires out to other baffled “unnaturals” (zombies, vampires, ghouls, and other utterly dead or dying creatures), each with his or her own devastating problem, all the while keeping an eye out for his own double-dealing killer.

Statistics, according to P. I. Shamble, show that these unnaturals are a serious problem:

According to the latest statistics by the DUS, the Department of Unnatural Services, about one out of every seventy-five corpses wakes up as a zombie…

With so many zombies and unnaturals around, sooner or later they will surely invade our sentences. Here’s how to root them out and get them the commas they deserve.

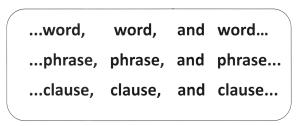

Lists of Words inside Sentences.

Key to success: Keep the parts of speech under control.

Private Investigator Shamble keeps these parts of speech under control with ease. Have a look:

1. List of 3 or more single nouns. Pattern: …noun, noun, and noun…

The world’s a crazy place since the Big Uneasy, the event that changed all the rules and allowed a flood of baffled unnaturals to return—zombies, vampires, werewolves, ghouls, succubi, and the usual associated creatures.

I reworded Anderson’s sentence to show that the list of nouns can be in the front of your sentence (the subject) or it can be in the back of your sentence (the predicate–as above).

Zombies, vampires, werewolves, ghouls, succubi, other baffled unnaturals, and other associated creatures have flooded the world since the Big Uneasy, making the world a crazy place.

2. List of 3 or more single adjectives. Pattern: …adjective, adjective, and adjective…

[The werewolf hit man] was a smelly, hairy, muscular guy, half-wolf and half-human.

Lists of adjectives can go in the predicate as above or in the subject as in the reworded sentence below:

That smelly, hairy, muscular guy, half-wolf and half-human, is the werewolf hit man.

3. List of 3 or more single verbs. Pattern: …verb, verb, and verb…

The worst characters [the unnaturals] were arrested, tried, and sentenced…

Keep in mind that verb tense in series must be kept parallel too!

Lists of Phrases inside Sentences:

1. List of noun phrases: (noun plus descriptive details written here in list form so you can see the parallel structure easier)

A dead detective,

a wimpy vampire, and

other interesting characters from the supernatural side of the street

make Death Warmed Over an unpredictable walk on the weird side.

Charlaine Harris, Book Reviewer, Death Warmed Over

Just before noon, the artist’s ghost manifested himself in our second-floor offices, wearing his preferred form:

long ponytail,

tie-dyed shirt, and

paint-stained jeans.

The main door burst open, and a terrified-looking man [a vampire] ran in. He wore

a dark overcoat,

gloves,

a black floppy-brimmed hat, and

oversized wraparound sunglasses like the ones old ladies wear after cataract surgery.

Robin spread out the legal forms on the signing table. “I have

the property deed to the real estate in Greenlawn Cemetery,

the plat marking the location of the crypt, and

the ownership transfer documents for Mr. Ricketts to sign.”

**Effective Writing Style Tip: for added interest, vary the length of each item in the series. Most often, put your longest item last, but you can vary this arrangement to make it more interesting. Try different arrangements to see how they work.

**Bonus: Here’s a double series of adjective/noun phrases.

Many haunters, underground dwellers, sewer jockeys, and walking dead

don’t mind

ramshackle appearances, piled garbage, or thick shadows . . .

2. List of verb phrases. Pattern: …verb phrase, verb phrase, and verb phrase…

After returning to life, I had

shambled back into the office,

picked up my caseload, and

got to work again.

***

In law school, she [Robin, Shamble’s secretary, and a ghost, of course] had been able to

pull all-nighters;

study,

write a term paper,

go to class in the morning,

take an exam,

hang out with friends in the afternoon, and

party at night.

***

Days of investigation had led me to the graveyard. I

dug through the files,

interviewed witnesses and suspects,

met with the ghost artist Alvin Ricketts and separately with his indignant still-living family.

3. List of adverb phrases. Pattern: …adverb phrase, adverb phrase, and adverb phrase…

Popular writer of his own zombie novels, Jonathan Maberry, reviewed Anderson’s Death Warmed Over using a series of adverb phrases. (Note his choice of omitting the serial comma!)

Master storyteller Kevin J. Anderson’s Death Warmed Over is

wickedly funny,

deviously twisted and

enormously satisfying.

Two decaying thumbs up!

Jonathan Maberry, Review of Death Warmed Over

While the rest of us have been warned not to overuse adverbs in our writing, book reviewers seem to get thrills and energizing chills from using them willy-nilly! Oh well, when you are famous, you follow a different set of rules. (Read: Don’t Use Adverbs? Book Reviewers Use Them!)

Finally, Remember Four Key Principles when Using Parallel Structure

- Look for series/lists in sentences. Good writers use them.

- Keep like parts of speech together in series/lists (parallel structure).

- Keep verb tense the same in a series of verb phrases.

- Use the serial comma (the comma before the conjunction).

Follow these simple guidelines, and you will keep the grammar meanies away forever!

Of course, there are more ways to use parallel structure, and future posts will give examples of these: Parallel structure with clauses coming soon.

**Effective Writing Style tip: Good writers use parallel structure to bring rhythm and flow to their writing.

And now, if you want to read more about the zombie invasion, here is another Kevin Anderson book., Hair Raising.

Your Turn:

What’s your favorite quote using parallel structure?

Can you use one of Anderson’s sentence patterns in your writing using your own topic-related words?

Posted in

English,

grammar,

Grammar-You-Can-See,

punctuation,

writing craft,

writing tips and tagged

effective writing style tip,

ESOL,

Kevin J. Anderson,

parallel structure,

parts of speech,

serial commas,

TESOL,

zombie books and grammar